INTERVIEW

LUCY VAN DORP (UGI): Some mutations do exist in the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2

The rate of mutation estimated in SARS-CoV-2 is similar to that in other related coronaviruses

Lucy van Dorp, a leading scientist from the UCL Genetics Institute (UGI) is a co-lead author of the latest study that identified 198 recurrent genetic mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 (novel coronavirus).

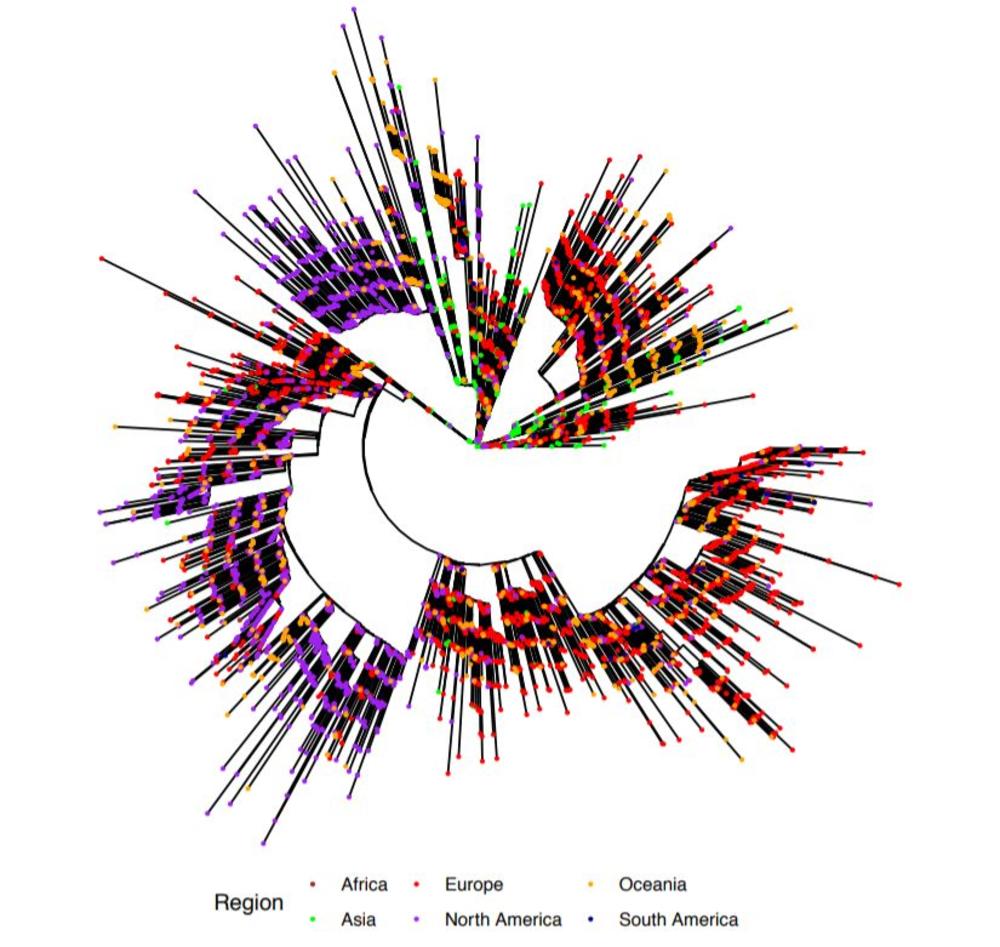

Her team did it by analyzing the genomes of the virus from more than 7,500 people infected with the novel coronavirus, and now their results could be widely used in efforts to produce drugs and vaccines against this vicious pathogen.

Dr van Dorp was very kind to respond to our request and share her thoughts on the SARS-CoV-2, the way it adapts to its human "hosts" and what we can expect from this virus in the future.

You are a co-lead author of the latest study that identified 198 recurrent genetic mutations in the SARS-CoV-2. What are the main and most important results of this study?

We find that SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for Covid-19, first began infecting humans towards the latter portion of last year. Since then it has gradually been accumulating changes or mutations, as all viruses do when they replicate. We find that around 200 of these mutations have occurred recurrently and independently. These may be very relevant to determining how the virus is adapting to human infection and are also important for informing drug and vaccine targets.

You did your research by analysing virus genomes from over 7.500 people from all over the world. I have to be honest, this sounds incredible, that this was done so fast, and on a scale so massive. When exactly did this become possible, and how much of a role do computers have in this?

Computational power is really everything and we are fortunate to make use of large-scale high-performance clusters at UCL. That said, the sheer speed at which virus genomes are being generated and made available is fairly unprecedented. Our analysis was on 7500 genomes. In the space of just a few weeks there are now well over 16,000.

As far as the SARS-CoV-2 mutations go, is this happening fast, slow or average, compared to similar viruses?

The rate of mutation estimated in SARS-CoV-2 is similar to that in other related coronaviruses. There is nothing to suggest SARS-CoV-2 is mutating faster or slower than we might expect.

One of the fascinating finds of this research is that there is probably no such thing as "patient zero", in the majority of the nations. Is this something new for the epidemiologists to work with, and how is this live pandemic analysys helping us understand the historic spread of some of the earlier viruses?

The first identified case is almost never the first case. Genetic data offers a way to distinguish between imported cases and local transmission chains. Our analysis points out that in most countries around the world there have been so many introductions, at so many times, that there are countless patient zeros seeding regional transmissions.

The mutations in SARS-CoV-2 are not evenly distributed across its genome. What parts of it are prone to mutations, as far as evidence we have so far go, and what parts are not? The interesting bits of the SARS-CoV-2, for those developing the vaccine, are probably spike proteins it uses to unlock the cell via the ACE2 receptors. Are these mutating in SARS-CoV-2? And, accordingly, is your research good or bad news, as far as reliable long-term vaccine development goes? Some of our inferred recurrent mutations do exist in the Spike protein, a region particularly important for virus entry into human cells. However, the exact functional consequences of these mutations are still unknown. Currently there is still limited genetic diversity that may result in evasion of a vaccine; however, it is important to keep monitoring this. Other regions of the genome are fairly conserved, particulary some of the other structural proteins, and these may also offer useful drug and vaccine targets.

Historically, where do mutations usually lead viruses? Do they usually become more or less deadly and contagious? And is there any evidence at all that points in which direction SARS-CoV-2 is going?

We are still really in the early days of the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 meaning it is difficult to make long term predictions. It is very possible there will be mutations which result in higher transmissibility of the virus but it is currently too early to tell.

How organized is the scientific community, as far as sharing data like this goes? For example, do you have any information if teams working on producing vaccines are using your data to modify their own approach?

We are currently working with a team of human geneticists exploring possible druggable targets. This is just one example and on the whole there are many large-scale collaborative efforts across scientific disciplines interested in the same question. The large amount of genetic data from SARS-CoV-2 will certainly aid these efforts.

Is there any way at all this virus could have been "made in a laboratory" by using genetic engineering?

Current evidence suggests the most likely scenario is that SARS-CoV-2 existed in an animal reservoir before switching into a human host. We do not yet have a good idea of what this animal reservoir was. To date the closest sequenced virus genome is one in circulation in horseshoe bats, though this is likely still too distant to be the intermediate host.

Plainly, do you expect there will be more money invested in science after this pandemic?

I hope so!

How important are viruses and bacteria for human evolution, and how have pandemics like this one shaped, and are shaping, our species?

Pandemics have had an enormous impact throughout our history, with infectious diseases likely the number one killer exceeding those that have died as a result of wars or famine. This is not the first pandemic and it won’t be the last. Plague, cholera and influenza have all been responsible for very significant pandemics within the last two centuries.

Bonus video:

(Igor Ćuzović)

Uz Espreso aplikaciju nijedna druga vam neće trebati. Instalirajte i proverite zašto!